VI. HISTORY REPEATS ITSELF

“Nothing happens, twice.”

Vivien Mercier famously commenting on Beckett’s two-act play, En attendant Godot.

In L'eclisse events may repeat or mirror themselves. Not only do events or people engage in a kind of “twinning,” but Antonioni attempted to double the entire film. Antonioni had originally proposed to the Hakim brothers, the eventual producers of L'eclisse, that two films be made: one from the viewpoint of Vittoria and the other from Piero’s point of view. Antonioni’s unique proposal was rejected, and only “Vittoria’s film” was ever made.

The first scene of the film--the dissolution of a relationship, the reason for which is left unexplained--is also the last scene of the film, “unexplained.” (The most poignant act of repetition occurs each time L'eclisse is projected, when--for one more time--Vittoria and Piero fail to meet.) Indeed, such motifs as twinning, redundancy, duplication, and recurrence may be seen as organizing principles supporting the structure of the film. Brunette writes of “rhyming,” a term that lyrically describes this ubiquitous tendency in L'eclisse of one scene to rhyme with another. Likewise, Robert Lyons has written that “[Antonioni] employs both the mise-en-scène (juxtaposition of characters and objects within a frame) and the montage (juxtaposed shots to develop a logic) in order to create the contrasts which will suggest his meaning.” Lyons also appears to use the term “parallel situations”--scenes that repeat a particular motif and that play one upon the other--in a manner similar to my use of the term, “mirror event.” Bondanella refers to “the principle of repetition with variation,” a “structural principle” that Bondanella states is utilized by directors including Antonioni, Rossellini, and Fellini (The Films of Roberto Rossellini, p.105). The mirroring does not limit itself to the confines of L'eclisse. As I have repeatedly observed, what occurs in Antonioni’s first film reoccurs in his last. The bar in the Eur in L'eclisse with the nondescript piano instrumental emanating from the jukebox is the same bar as the one at the Verona AeroClub with the lazy idyll playing on the jukebox is the same bar in Zabriskie Point in a small town in the Southern California desert with “The Tennessee Waltz” hanging limply in the air.* “Twice-Told Tales.”Such mirror scenes hark back to the earliest days of cinema, when Soviet filmmakers placed special emphasis on montage/editing. The juxtaposition of one shot with another in a given scene, as well as the juxtaposition of one scene with another became a means of suggesting meaning, as one cinematic image builds upon another leading to an accretion of potential meaning. Such a method of fabricating significance is not declarative, but may instead be seen as reticent, even shy, a style that seems to suit Antonioni well. Juxtaposition as a tool to imply meaning may be trivial as in the case of the cut from the seduction of Vittoria in the apartment of Piero’s parents to the phallic steeple of the unusual building in the Eur , or juxtaposition may operate on a more generic level, as in the comparison between two different worlds, that of Piero and the Borsa with the “natural” world of Vittoria.* As Ernest Lindgren in The Art of the Film has written of Griffith and Eisenstein:

Whereas Griffith appears to have thought predominantly in terms of the scene, and of the relationship of one dramatic scene to another, the Soviet directors tended to think far more in terms of the relationship between single shots, single fragments of action, to express implications, comments, ideas, overtones of significance. They were much preoccupied with the possibilities of the fact that by joining one shot to another it is possible to create a tertium quid, a third something, which is not present in either of the shots separately, and which is also something more than the mere sum of them.

Antonioni relies on both of the above strategies of montage/editing. Such strategies allow for a linkage between seemingly discrepant scenes and objects, a child’s bed, a magnifying glass, a necklace of glass balls, and a female pygmy trapped within a pen. To these two strategies Antonioni adds a third technique of juxtaposition across or between his individual films.

On a macroscopic level the entire relationship between Vittoria and Riccardo mirrors that of Vittoria and Piero. As noted in the first paragraph of this book, L'eclisse begins and ends with their respective ruptures. On a microscopic level, the first act committed by Vittoria on film, the rearrangement of bric-à-brac within the picture frame, is repeated throughout L'eclisse. This act reoccurs--an act of perseveration, if you will--when Vittoria later attempts to find the right spot, “il punto giusto,” for the fossil plant, as well as her repeated manipulation of the objects within the water barrel.*

Many more examples of repetition occur, some seemingly trivial. Again, in the opening scene of L'eclisse Vittoria is “xeroxed” as we see her image reflected in the shiny pavement of the floor of Riccardo’s apartment, in the apartment’s window as Vittoria looks out at the Eur, as well as in a mirror hung on a wall in which she is is cleaved in two--impaled--by a vertical wooden decorative element of the mirror. (Little snippets of film--images--whose mystery haunts the history of art and humankind: the Divided-Self.)

The Splintered Self

The scene in the Piazza di Pietra in which Vittoria almost purchases a “skin” for Piero might seem at first inconsequential and unmotivated until we remember that earlier in the film Vittoria’s mother bought pears in the same piazza from a street vendor.* The two scenes are not perfect mirror images of one another, but because of their subtle differences the scenes help to highlight the differences rather than similarities between mother and daughter. Vittoria, after all, wishes to buy a gift for someone else, and she does not haggle with the vendor, as does her mother. In Il deserto rosso Antonioni will, however, again place his actress, Monica Vitti, beside a produce stand—this time in Ravenna—where she will again encounter a man she cannot love, and again buy no fruit.

With regard to Vittoria’s offer to buy a chamois and Piero’s refusal of the offer, there is a selection of ironies from which to choose. Does Piero “know” that he will not require the chamois because in only a matter of hours his car will be wrecked? Or does Vittoria offer the cloth because she knows the car will soon be pulled out from a lake?

A curious nexus of associations link the Bestiola and Vittoria, transforming them into imperfect mirror images of one another. The Bestiola is an old girlfriend of Piero who will be replaced with a new one (Vittoria will in turn be reciprocally abandoned at the end of the film). Piero arranges an evening meeting with the Bestiola at “il solito posto” (the “same old spot”), the exact expression which he will later use with Vittoria when referring to their habitual meeting place at the Eur construction site. Piero almost forgets his evening rendezvous with the Bestiola. (The Bestiola waits for Piero while standing on the sidewalk outside his office, a case of being nearly literally “stood up.”) By the end of the film, Piero will achieve the definitive “forgetting” of his evening meeting with Vittoria. In Vittoria’s case, Piero will stand up a woman who he will never know has also stood him up. Both Vittoria and the Bestiola will vanish, exiting from side doors of the film with nary a goodbye nor fare-thee-well. Vittoria seems to almost fill the very shoes of the Bestiola, for it is on the sidewalk in front of the window grill of a storefront beneath Piero’s office that we last see Vittoria, within feet of the same spot where last we saw the Bestiola, also in front of an identical storefront grill.

I am not the first to stand here

Both women have recently become darker. In the Bestiola’s case, she has dyed her hair black. In the case of Vittoria, it is the skin that has itself been tinted black. (In L’avventura there is a dispute in Troina between the pharmacist and his wife as to whether the mysterious “forestiera” [“foreign woman”] is blond or brunette; Claudia herself briefly tries on a wig at the Villa Niscemi temporarily transforming herself from a blonde into a brunette.) As the Bestiola’s name implies, she is a wild animal. In Vittoria’s last scene with Piero, Vittoria will briefly transform herself into a lioness not unlike the female lions in the photo on the wall of Marta’s apartment. Antonioni might as well be tapping us on the shoulder saying, “Look, Vittoria and the Bestiola are interchangeable.” One might wonder whether it is not only Vittoria, but also the Bestiola who is trapped inside Piero’s novelty pen. When Vittoria first discovers the pen, she examines it carefully, not simply flipping the pen up and down about its vertical axis--thereby disrobing and robing a single, shrunken woman--but also, rotating the pen one hundred and eighty degrees back and forth along its vertical axis, revealing two trapped women (or one woman seen from both front and back?). This carefully choreographed dance--no comic burlesque, but a tragic pirouette--representing a POV shot from Vittoria’s perspective, is shown in close up, as much for our benefit as for Vittoria’s. The pen is a microcosm of the entire world of L'eclisse, one in which there is a view, not of one miniature woman, but of two.

Vittoria repeats the mantra of “I don’t know” (“Non lo so”) to both Riccardo and Piero at the beginning and near end of film. Both Vittoria and Piero visit their childhood homes. Vittoria and Piero stand directly behind an older couple seated at the outdoor piano bar of the Eur, a senior mirror image of themselves.

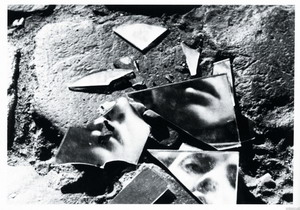

Obsession-compulsion is an essential aspect of the erotomania that characterizes many of the men in Antonioni’s film, including Piero. Likewise, addictive behavior is part of the Borsa which we have seen is also infused with Eros. (Remember that Piero has called himself both a gambler and a whore.)26 In the coda, figures we have seen earlier in the film such as the jockey reappear. The final illumination of the streetlight at the end of the film is a repetitive act, occurring at the same time each evening. Other examples have already been given in the context of such thematic concerns as the relationship between people and objects, or the theme of metamorphosis. These latter themes are closely related to such concerns as duplication and splitting. A literal act of mirroring occurs in the opening scene of L'eclisse when we see Vittoria from behind as she stands before a mirror, Riccardo in his incarnation as a chair captured in the same frame, a look of anguish on Vittoria’s face reflected in the mirror. Antonioni’s preoccupation in many of his films with mirror images involves a kind of mitotic splitting of one being into identical halves. (A dramatic example of splitting into multiple parts occurs in the early Antonioni documentary, Superstizione, in which there is a shot of multiple aspects of a woman’s face seen in the multiple shards of a broken mirror lying on the ground; see p. 88 of Mancini and Perrella’s Michelangelo Antonioni. Architetture della Visione.)

The Splintered Self

In The Passenger, the doubling phenomenon resembles not so much mitosis, but something less biological and more literary: body snatching. Even the nameless Girl of this latter film may be split in two, for is there not reason to believe that she is but one more Antonionian creation who is not what she seems, a “double” agent?

J.W. Kearns points out that the name commonly ascribed to the nameless Photographer of Blow-Up, “Thomas,” means “twin,” whose etymology may reflect the Hebrew word for twin, “תאום” (“teom”). As is the case with many publications concerning Blow-Up such as the Lorrimer Publishing edition of the script, the Photographer is referred to as “Thomas,” although no such appellation is present in the film itself.

The scene with Vittoria and Piero in her childhood bedroom is a complex and subtle illustration of several of the above themes. The scene mirrors a later scene in which Vittoria and Piero will meet in the apartment of Piero’s parents. Shortly after entering the latter apartment, Vittoria will sit down beneath a large painting of a young girl. Within minutes, Vittoria will walk through the room where Piero spent his childhood (still containing an artifact of adolescent sexuality, the novelty pen of the nude woman) and eventually go down a one-way alley leading to the dead-end of the bedroom of Piero’s parents. The apartment is conveniently empty, no parents, the customary trap prepared by the teenage boy for the seduction of the young girl who is his prey. It is then in the very bed of Piero’s parents that the girl, prostrate on her back, will be taken. Piero is an adult male. He does not bring Vittoria to his big-boy, grown-up apartment (which Vittoria herself refers to as Piero’s “pied-à-terre”)--but to the home of his parents for their get-together. This is not some form of literal, statutory rape, but a much more literary, peculiar, and mysterious form of child abuse. (How curious, how odd, that in this adult love story there are two reciprocal scenes in which the lovers find themselves together in their childhood rooms of their parents home. We see Vittoria’s present, “adult” apartment in the Eur, but are denied a mirror view of Piero’s present abode. Does it even exist? Does he really live with his parents?)

Throughout L'eclisse Vittoria is intermittently presented in a childlike guise. For example, Antonioni carefully notes in his screenplay that when Vittoria exits from Riccardo’s apartment in the very first scene that she “walks swinging an arm in the manner of a child.” / “Cammina dondolando un braccio come i bambini.” Seated beneath the painting of a little girl in the apartment of Piero’s parents, Vittoria’s reticent posture and behavior are reminiscent of a little girl, a girl who nevertheless will within minutes be making love with an ostensibly grown man. Piero chides her for such behavior, but it is Antonioni who is obstinate in his desire to juxtapose Vittoria with young girls: immediately after being asked by Piero if she is going to sit in that chair beneath that picture all day, Vittoria arises only to walk into another room and stop before a photograph of three unidentified children (girls?) in whose frame covered by glass we see Vittoria’s reflection. Vittoria places herself in such a manner that her head completely superimposes or “supplants” that of the three children. As Vittoria’s head is now contained within the picture frame, she has momentarily managed to both literally and figuratively substitute herself for the children becoming the sole subject matter of the portrait.* Already mentioned was the background image framed by a door of a presumptive mother holding the hand of her young daughter as Vittoria exits from Piero’s office in her final scene. Vittoria, like the children playing in the Eur park, also plays with the water sprinkler. In her mother’s apartment she listens to the radio reports of the market crash with a child’s wonder, and retreats timidly at Piero’s incomprehension of such naïveté. Her unadulterated enthusiasm for the plane trip to Verona is childlike (reminiscent of the childlike joy with which David Locke-Robertson spreads his wings as he flies in the aerial tram over Barcelona).27

Even Vittoria’s manner of kissing is immature. Not a single kiss in all of L'eclisse is passionately given by Vittoria without some awkwardness or reserve. Adriano Aprà contends (in an interview contained within the documentary by Sandro Lai, Michelangelo Antonioni: The Eye That Changed Cinema, a documentary which in turn is included as a supplement in the Criterion Collection DVD of L’eclisse) that although Vittoria and Piero may not love one another, there nonetheless exists an erotic, sexual tension between the two. Erotic tension is difficulty to measure, and there is no objective evidence in the entire film of a mature, uninhibited, reciprocal, and unequivocally passionate sexual exchange between the two. Indeed, what is surprising is how unerotic and neutered is the relationship of Vittoria and Piero. As already suggested (vide supra, Chapter 2), Vittoria’s libido seems—to employ Freudian terminology—more directed towards the object of the broken piece of wood than towards the broken, narcissistic man, Piero. Piero’s superficial default position with regard to women is sexual. What must be particularly frustrating for such a man is that such a position will not ultimately engage such a woman as Vittoria in any meaningful way. The enigma of L’eclisse may depend in some fundamental way on the fact that the tenuous bond that binds Vittoria and Piero is not primarily sexual, but instead may arise from another kind of longing, presexual and primordial, or a kind of longing found on the other bank of sex, sublime and other worldly. There is, instead, only the most ambivalently expressed wish to love. Towards the end of L’eclisse--while in the grassy field of the Eur in front of the “impossible building”--after a limp, flaccid proposal of marriage by Piero, Vittoria responds, “Vorrei non amarti, o amarti molto meglio.” / “I wish I didn’t love you, or I wish I loved you better.” This places Vittoria in a purgatory of paralyzed ambivalence, not quite the hell that Dostoevsky reserves for those who cannot love at all, the same hell that Sgt. X in the haunting short story by J. D. Salinger, “For Esmé – with Love and Squalor,” refers to from The Brothers Karamazov. With regard to sex per se, the only perfunctory, presumed act of sex that may have taken place occurs in an off-screen ellipse in the apartment of Piero’s parents, a token act so insubstantial--one we do not witness and, hence, an act that is invisible--that we cannot even be certain if it was consummated, let alone, “good sex.” At the literal end of the day, there is neither much love nor much sex. There is, in fact, nothing much at all, which may ultimately and simply explain why neither “lover” shows up at film’s end for a loving or merely sexual encounter for which there is no foundation or will. When in L’eclisse does Piero turn towards Vittoria and--gazing in her eyes--breathlessly whisper, “Dovrò dunque assembrarti al dì d’estate?” / “Shall I compare thee to a summer’s day?” When does Vittoria hear the words whispered, as if a prayer, “Nessuno, neanche la pioggia ha così piccole mani . . . .”? / “(i do not know what it is about you that closes and opens; only something in me understands the voice of your eyes is deeper than all roses) nobody, not even the rain, has such small hands”? When—with the music of Georges Delerue soaring plaintively in the background—does Piero pledge to Vittoria as if uttering a sacred vow, as Paul utters to Camille in Godard’s Le Mépris: “Je t’aime totalement, tendrement, tragiquement.” (“I love you totally, tenderly, tragically.”) The injunction in Antonioni’s films against genuine declarations of love creates a shortcut to an alternative destination, that of death, the motto for which—instead of “I love you”—is: “And, surely, for this, you shall die.” In Malcolm Lowry’s novel, “Under the Volcano”—a tale told on the Mexican Day of the Dead—the doomed, principal protagonist collides in a kind of accidental, provident “collision” with a famous, foreboding epigram: “No se puede vivir sin amar” / “One cannot live without love.” The protagonist’s subsequent death validates the truth of the epigram—the sentence—a sentence which in a word-play is also a verdict which carries a mandatory punishment, that of the death penalty. Have Vittoria and Piero been convicted at the end of L'eclisse—wiped off the silver screen—for their failure to love?

Vittoria never exhibits the glorious exultation that Claudia exudes after embracing Sandro outside of Santa Pantagia aside the train tracks in L’avventura. Instead, Vittoria appears to more freely make love when a pane of glass separates her from her lover, or when she may use her hands--the “pieties of hands” referred to by Hart Crane--as the instruments of lovemaking as in the scene in the apartment of Piero’s parents when their fingers become entwined. (Both the kissing through glass and the lovemaking between hands are reprised later in L'eclisse in the final scene between Vittoria and Piero in Piero’s office.) Vittoria’s preference is to explore the world with hands and not lips (Mancini and Perrella give examples in their book of Antonioni’s preoccupation with hands in many of his films. Within L'eclisse there is, to use Brunette’s term, a “rhyming” between the hands of the dead Drunkard and those of the doomed lovers.)28 As we shall soon see it is not just Vittoria’s behavior, but her stature that is also that of a child.

The pieties of hands

Although Antonioni is not known as a director whose focus is on children (to my knowledge, Antonioni, himself, is not known to have fathered any children), subtle and not so subtle references to childhood recur throughout L'eclisse. In fact, the intrusive appearance in an unmotivated manner of an unidentified child or children is a favorite, recurrent image in several of Antonioni’s films. Not long after the very beginning of L'eclisse, as Vittoria and Riccardo are walking in the Eur towards Vittoria’s apartment on the Viale dell’Umanesimo, a small, unidentified boy suddenly darts in front of their path. Riccardo smiles and pats the boy on the head as the child exits off screen and out of the movie. The appearance of the boy is unmotivated, starting from nowhere and leading to nowhere. (Or does the boy rapidly grow up and reappear as the handsome young man who later in the film bisects the path of Vittoria and Piero as they too walk in the Eur?) A remarkably similar event occurs towards the beginning of Blow-Up as the Photographer exits from the back door of his studio to visit his neighbors, the artist of abstract paintings and the woman, played by Sarah Miles, with whom the artist lives. As the Photographer crosses a small alley separating their two studio apartments, we see a small child--apparently a boy--standing behind a gate staring at the Photographer as he passes. The Photographer takes obvious note of the child, bending his torso and turning his head to regard the child as he walks by. In Le amiche, Antonioni combined in one scene two favorite recurrent images, that of children together with people of the cloth. While returning by train to Torino from her trip to the Ligurian Sea, the troubled heroine, Rosetta, walks down the train’s corridor. Sighting a group of young school girls and a nun seated in a cabin, she stops and gently caresses the chin of one of the young girls. Likewise, in the very opening shot of I vinti, a nun holding the hand of a child is seen in the background ascending a Montmartre stair walk (Passage Cottin). Indeed, in all three of the episodes of I vinti there is a brief, unmotivated appearance of a child who crosses the path of the main character. In the Italian episode, Claudio is comforted by a young girl while he lies dying of an “internal lesion” in the stands of a soccer stadium. Towards the conclusion of the English episode, a young girl pops up like a Jill-in-a-box from out of nowhere and throws a ball to the would-be murderer, Hallan, while he stands on a London sidewalk. The appearance of these young children in an analogous and unmotivated manner in several different Antonioni films may be seen in a generic sense as a typical Antonionian motif: the reappearance of a particular image in Antonioni’s films that has no certain significance, but instead defines a certain pattern. As I have repeatedly done in this book, the study of Antonioni’s films becomes the categorization of such motifs.

When Vittoria exits from the stock market early in the film to meet her mother, we briefly see and hear a man in the Piazza di Pietra offering to exchange dollars for--one assumes--lira. In the same shot we then see the back of a woman who holds the hand of a young girl--presumably mother and daughter--as they walk towards Vittoria who is walking across the piazza in the opposite direction towards us and the camera. The camera angle briefly permits the superimposition of the young girl upon Vittoria (as later the Drunkard will be momentarily superimposed upon Piero as they cross each other walking in opposite directions down a sidewalk). At this moment we again hear the chant of the money changer crying, “Cambio! Dollari!” presumably a literal reference to the exchanging of dollars for lira. As Vittoria approaches the mother and daughter, Vittoria then looks down upon the young girl and turns her head slightly to allow her gaze to follow the girl as they pass each other in opposite directions. As the mother and daughter continue walking into the screen background, the girl herself turns her head to look back upon Vittoria.

Haunted by the gaze of children

In the same shot the money changer then briefly approaches Vittoria who declines his offer. It is then that Vittoria will encounter her own mother. An exchange may have indeed taken place, not on a literal, but on an almost magical plane. (Chatman reminds us that in Blow-Up the young woman played by Vanessa Redgrave is last seen under a shop sign, Permutit. “Cambio” becomes such a sign, the auditory counterpart of “permutit.”) As already mentioned, a most subtle and evanescent appearance (and disappearance) of a presumptive mother and daughter also occurs in front of Vittoria just before she exits from Piero’s office building and then from L'eclisse itself (the same mother and daughter who earlier appeared in the Piazza di Pietra?). The repeated appearance of the nurse and stroller in the Eur is but another resonance of woman-child. (This confrontation between a woman and her child self will reappear in the guise of the Sardinian fantasy in the film that immediately follows L'eclisse, Il deserto rosso.) These subtle examples of the fleeting appearance of mothers and daughters as they cross Vittoria’s path are but further instances of the twinning, repetition, and metamorphosis which occur throughout L'eclisse. The subtle, unmotivated, and inconspicuous appearance of these children is such that their images approach being subliminal, in turn raising the larger question of how much of the entire movie depends on an almost silent, invisible, pre-discursive appeal to the subconscious.

Four years later Antonioni will again reprise the intrusive image of a mother and daughter crossing paths with a film’s chief protagonist. In Blow-Up, as we see the Photographer returning from Maryon Park to the antique shop after shooting the unidentified couple in the park, we see him approaching the shop from a point of view which is framed looking outward through the shop’s main door to an otherwise empty street. Suddenly, from off camera a woman pushing a pram appears who the Photographer turns his head to look upon. This sly, little joke on Antonioni’s part also reminds us of Piero’s turning his head to ogle the nursemaid and her pram while walking in the Eur of L'eclisse, as well as the deliberate turning of Vittoria’s head as she looks down upon the young girl passing by in the Piazza della Pietra. (The woman with pram outside the antique shop of Charlton is wearing a sweater with a pattern of black and white stripes, again a small smile on Antonioni’s lips as he tells us not to forget the passaggio zebrato of the fateful Eur street corner.)

In the magisterial finale of The Passenger at the Hotel de la Gloria, the Girl stands at Locke’s window looking out at the scene before her. Locke enters the room and asks her what she can see. The Girl replies that she sees an old woman and a young boy arguing about which direction to take. Vanoye in his book, Profession : reporter, refers to this description of old woman and boy as a “motif de l’adulte et de l’enfant” (my italics), and reminds us of other evanescent scenes concerning children that appear throughout The Passenger (as is the case with L'eclisse). The very beginning of the film concerns the sudden appearance of an African boy seated in Locke’s Land Rover who will give directions on how to reach the guerrilla base in the desert. In the Umbraculo of Barcelona while children are seen and heard playing in the background, the old man whom Locke encounters begins what is a conversation between two strangers with a philosophical rumination on children and the vicious circles of history. Later, in keeping with an abiding preoccupation on Antonioni’s part with autos and death—a preoccupation Antonioni shared with the Japanese director, Mikio Naruse—Locke almost runs over a group of children with his muscle car, the white convertible Cyclone, while fleeing Almería.

In Il deserto rosso, the film which Antonioni made immediately after L'eclisse, the heroine of the film, Giuliana, suffers from a severe psychological ailment in which her behavior might be described as “childlike.” Early in Il deserto rosso, Giuliana tells her would-be paramour, Corrado, of a “girl” (“ragazza”) whom Giuliana had met when she was hospitalized after a supposed auto accident. Giuliana later confesses to Corrado that the “girl” was herself. (We may also presume that Giuliana had also lied regarding her “hospitalization”; while she may have indeed had such an accident, the car crash may have been a suicide attempt and Giuliana’s subsequent hospitalization may have been in a psychiatric as opposed to a medical ward.) Similarly, when later in the film Giuliana tells her son the “bedtime story” of the Sardinian fantasy (reenacted by Antonioni in an episode shot on the island of Budelli), the young girl of the story may be presumed to be a thinly veiled projection of Giuliana talking about herself. As Arrowsmith has pointed out, in Il deserto rosso, the explanation for the childlike behavior may relate to the psychological phenomenon of “regression,” in which a person with a psychiatric disorder might retreat to behavior of a more primitive nature that had previously been exhibited in the patient’s childhood. With regard to Vittoria and L'eclisse, the phenomenon of regression cannot so easily explain the nexus of connections between Vittoria and children.

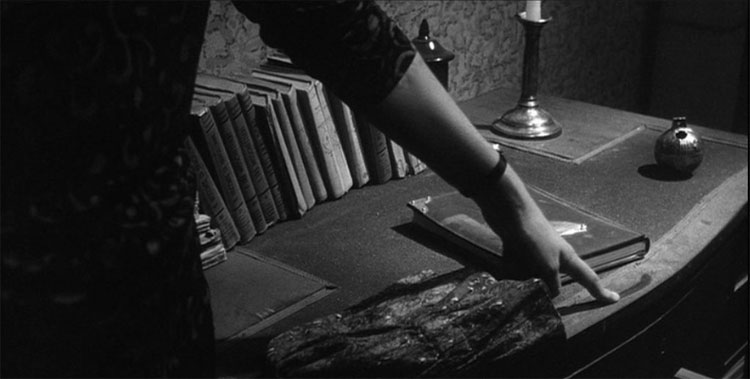

It is in Piero’s bedroom in his parent’s apartment that Vittoria discovers her doppelgänger, the woman imprisoned in the pen.29 In the earlier meeting in Vittoria’s childhood bedroom, Piero also discovers an object with which he casually plays, an apparent magnifying glass.* Piero’s manipulation of the magnifying glass is so deliberate an act that one must ask, “What is Antonioni up to?” As has already been discussed, one of the functions of mirror scenes is that they help either reinforce, decipher, or invite contrast with other scenes. In this light, one might say that a girlie, cheesecake novelty item from Piero’s childhood room speaks volumes as to who Piero is. Contrariwise, a magnifying glass next to Vittoria’s childhood bed conforms with our view of her as someone who is interested in looking closely at the world. There is, however, another way of looking at these two scenes--as it were--under a microscope. The scene in Vittoria’s bedroom begins with Vittoria wiping dust with her finger from the surface of a chest of drawers, upon which chest lies an apparently prized book—one with ornate metal corner protectors—perhaps a particularly relevant religious work such as Ecclesiastes or a profound secular meditation on life and death such as “Hamlet.”

Dust to dust, what is this quintessence of dust?

Vittoria then lays down on her small childhood bed. She expresses amazement that she was ever able to fit in such a bed, to which Piero responds that surely she was shorter when she was a child. Vittoria laughs aloud at Piero’s reasonable hypothesis, exclaiming, “Macché! Mia madre dice che a 15 ero altissima, molto più d’adesso!” (“Nonsense! My mother says that at fifteen I was very tall, much taller than now!”) Indeed, on the wall beside Vittoria’s bed is a string of large glass balls, an odd adornment for a bedroom, one that resembles a necklace for a giant woman in a Brobdingnagian world (not unlike the necklace worn by Vittoria’s mother in the same scene, small decorative balls on a string hung around the neck).* Simply put, Vittoria is shrinking. Vittoria’s unusual comment prompts us again to ask, “What is Antonioni up to?” A simple response would be that Antonioni merely wishes to reemphasize the ignorance of Vittoria’s mother. She is, after all, a vulgar person who resorts to primitive explanations for the market’s fall (“It’s the socialists!”), spreads salt on the trading floor of the Borsa as a superstitious rite, throws things in anger at the traders, and most importantly is entirely indifferent to the needs of her daughter. (The mother’s reaction to hearing of her daughter’s breakup with Riccardo is to lament that a potential source of money may now be lost.) I believe that a more elegant answer lies elsewhere, and that it is again necessary to consider the two mirror scenes together. After Vittoria’s amused exclamation that she is shorter as an adult than as a child, Piero tries to kiss her. Vittoria rejects his advances and arises from the bed, after which Piero picks up the magnifying glass and begins playing with it. (He does not seem to recognize its function insofar as he merely twirls it in his hand rather than looking through its lens.) Magnifying glasses make small things look bigger. Taken together, the two scenes--Vittoria and Piero, first in her childhood room, and later in his--document the progressive shrinking of Vittoria from her apogee in adolescence to her perigee in adulthood as a shrunken object of desire trapped in a pen. The magnifying glass becomes a conceit that yokes the two scenes together. As the shrinkage continues, Vittoria will eventually disappear from the face of the film.

Much earlier in L'eclisse, Vittoria hammers a nail into her apartment wall in order to hang the fossil plant. The nail is placed at a ridiculously low spot, one that would be best suited for either a small child or a little person. (One wonders whether Antonioni also intended that this image be a violent one, for Vittoria hammers the nail into the shadow of her head silhouetted on the wall.)

Nailing the head of a little girl’s shadow

Only minutes later, Anita enters Vittoria’s apartment, complaining of the banging noise. Anita then changes the subject, remarking that she herself has gained weight, whereas Vittoria is now thinner (“Sei dimagrita.”). Soon, Vittoria will weigh nothing at all.

Another peculiar reference which possibly bears on the issue of Vittoria’s height occurs in the small airplane en route to Verona. Vittoria asks, “Che tipo di nuvola è quella?” (“What type of cloud is that?”), to which Anita’s husband responds, “Sembra un nembo-strato, ma in genere sono molto più basse.” / “It looks like a nimbostratus, but they’re usually at a lesser elevation.” Anita then invokes a kind of unwitting transformation of Vittoria when she remarks, “Tu sembri un nembo, come le altre.” / “You seem like a nimbus, just like the others.” One remembers however that the word “nembus”--as opposed to “nimbostratus” refers in classical mythology to “a shining cloud sometimes surrounding a deity when on earth.” (Webster’s Dictionary). Anita confirms this allusion when she then tells Vittoria, “[il nembo] sembra illuminato da dentro.” / “[The cloud] seems illuminated from within.” In a subsequent scene at the apartment of Piero’s parents, Antonioni in the 1964 (Einaudi) screenplay reinforces the comparison between Vittoria and a bright cloud by writing (p. 424), “Vittoria, che stava allontanandosi verso una parete scura, si volta: nel suo vestito bianco è come una macchia luminosa.” / “Vittoria, while retreating towards a dark wall, turns around: in her white dress she appears as if a luminescent spot.” After landing in the small Verona airport, there is a shot of Vittoria standing alone against a backdrop of clouds, Vittoria’s head appearing to be “in the clouds.” In the Lane 1962 screenplay of L'eclisse (p. 57), Vittoria’s mother addresses her daughter in one scene--a scene that was either never shot or edited out of the final film--as “Stellina,” the Italian diminutive for little star. In such a light, Vittoria’s disappearance at the conclusion of L'eclisse makes her the lost Pleiad, hiding not from Orion, but from men such as Riccardo and Piero. (Continuing in an astronomical vein, the Lane screenplay compares Piero to a “bolide” [meteor], which in the colloquial Italian of the 1960’s also referred to a fast car. p. 45).

Curiously, Vittoria may not be the only person in L'eclisse who is shrinking. In the earlier scene already discussed between Piero and the secretary, Maria, Piero had remarked that “I tramonti non scappano.” (“There will always be another sunset”). Piero then makes a remark to Maria that is left untranslated in an American video release of L'eclisse (Los Angeles: Connoisseur Video Collection, 1988, ©1962): “L’altra sera stavi al Pincio con un piccoletto alto 1.20-1.30.” (“The other evening at sunset you were at Pincio [a Roman hill] with that pip-squeak [ometto in the original screenplay Sei film published by Einaudi, as opposed to the word piccoletto actually uttered by Piero in the film] who’s only about 5 feet tall.”)* Again, the irony of Piero’s remark is that he too will soon have a date at dusk with someone whose height is at issue. One is again reminded of Ted Perry’s observation regarding “distortions of scale and perspective.”*

In addition to references to the height of persons and things, there are also references to weight as well. On two occasions, Ercoli, Piero’s boss, refers to the market as “pesante” (“heavy”). On the day of the market crash, Vittoria discretely follows at a distance the obese man who has lost 50 million lira in the crash as he purchases medication in a pharmacy. Of all places, Vittoria observes the man while she hides behind two small pillars while standing upon a commercial scale set beneath a clock (a meditation on the physics or metaphysics of mass and time, time and space), into which she deposits a coin and weighs herself. The market has lost weight and--as already mentioned by Anita--so has Vittoria. With regard to L'eclisse, “minimalism” may describe Antonioni’s artistic style . . . as well as Vittoria’s fate.